Tail risk is the chance of a loss occurring due to a rare event. It is defined by the concept of standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. Volatile assets have higher standard deviations because there is greater variability in their observed returns. Tail risk is something that investors need to keep in mind, and there are a few different ways to mitigate its impact on an investment portfolio.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The chance of a loss occurring due to a rare event, as predicted by a probability distribution. |

| Colloquial definition | A short-term move of more than three standard deviations. |

| Standard deviation | A metric that shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. |

| Volatile stocks | Have a high standard deviation. |

| Steady stocks | Have a low standard deviation. |

| Tail risk and returns | Tail risk is responsible for most returns over time. |

Standard deviation

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance. It is defined by the concept of standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. A volatile stock will have a high standard deviation, while a stock with a steady value will have a low standard deviation.

A short-term move of more than three standard deviations is considered to instantiate tail risk. Investors are most concerned with 'left' tail risk, or the likelihood that observations fall three standard deviations below the average expected return. Volatile assets have higher standard deviations because there is greater variability in their observed returns. In the event of a left tail market movement, returns for these assets could be significantly impacted.

There are strategies that investors can adopt to curb the losses predicted by left tail risk, such as investing in managed futures funds or taking different hedging positions. These strategies can provide significant value in the long run, not only to individuals but to the market as a whole.

Crafting a Winning Investment Portfolio: Sample Strategies

You may want to see also

Volatile assets

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance. It is the chance of a loss occurring due to a rare event, as predicted by a probability distribution. A short-term move of more than three standard deviations is considered to instantiate tail risk.

In the event of a left-tail market movement, returns for volatile assets could derail even more significantly. Strategies adopted by investors to curb the losses predicted by left-tail risk, such as different hedging positions, can provide significant value in the long run, not only to individuals but to the market as a whole.

Private Investment Firms: Managing Money, Making Profits

You may want to see also

Hedging positions

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance. This is also known as the chance of a loss occurring due to a rare event. Tail risk is defined by standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. Volatile stocks have a high standard deviation, while stocks with a steady value have a low standard deviation.

Microbusiness Investment: Your Guide to Making a Living

You may want to see also

Rare events

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance. It is defined by the concept of standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. Volatile stocks have a high standard deviation, while stocks with a steady value have a low standard deviation. Tail risk is the chance of a loss occurring due to a rare event, as predicted by a probability distribution. Colloquially, a short-term move of more than three standard deviations is considered to instantiate tail risk.

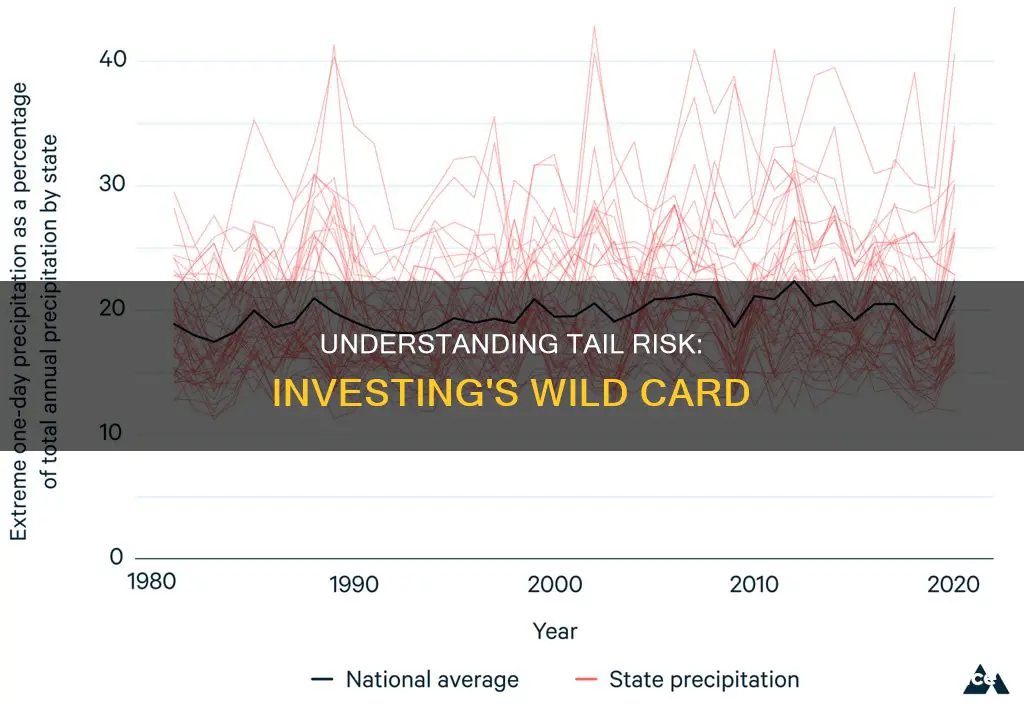

Tail risk is something that investors need to keep in mind when making investment decisions. It is technically the anticipation of rare events, or the probability of a very unlikely event occurring. By some estimates, market shocks have occurred about every three to five years over the past three decades, resulting in "fatter" tails than a normal distribution curve would predict. This means that tail risk happens more often than many investors might think and at an increasingly global scale.

There are a few different ways to mitigate the impact of tail risk in an investment portfolio. Strategies such as different hedging positions can provide significant value in the long run, both to individuals and to the market as a whole. For example, investors who want to trim their exposure to tail risks may invest in managed futures funds, which buy long and short futures contracts in equity indexes and can thrive during times of crisis in the markets. Additionally, history shows that preemptive analysis of tail risks in the wider markets can potentially curtail the effects of systemic shock on a spectrum of investments.

Savings and Investments: Smart Money Strategies for Beginners

You may want to see also

Long-term investment

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance. It is defined by the concept of standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average. Volatile stocks have a high standard deviation, while stocks with a steady value have a low standard deviation.

For long-term investors, it is important to keep in mind that tail risk is responsible for most returns over time. While it is inherently the probability of a very unlikely event, it happens more often than many investors might think. Strategies to mitigate tail risk, such as different hedging positions, can provide significant value in the long run. For example, investors who want to trim their exposure to tail risks may invest in managed futures funds, which buy long and short futures contracts in equity indexes and can thrive during times of crisis in the markets.

Building an Investment Portfolio: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Tail risk is the probability that an asset will perform far below or far above its average past performance.

Tail risk is defined by standard deviation, which shows how widely the price of an asset fluctuates above and below its average.

Investors are most concerned with left tail risk, which is the likelihood that observations fall three standard deviations below the average expected return.

By some estimates, market shocks have occurred about every three to five years over the past three decades, resulting in fatter tails than a normal distribution curve would predict.

Investors can mitigate the impact of tail risk by adopting different hedging positions, which can provide significant value in the long run.