The relationship between savings and investments is a key topic in economics, and one that has sparked much debate. The question of whether savings and investments are equal has been a source of controversy, with economists holding differing views. While some argue that savings and investments are only equal under conditions of equilibrium, others, like Keynes, assert that they are always equal. This controversy has been resolved, and there is now a consensus among economists regarding the relationship.

In economics, savings refer to the money withdrawn from an economy's total spending, while investments are the additions to this total spending. Savings are a form of leakage, as they reduce the amount available for consumption expenditure, while investments are injections, as they put money into the economic system.

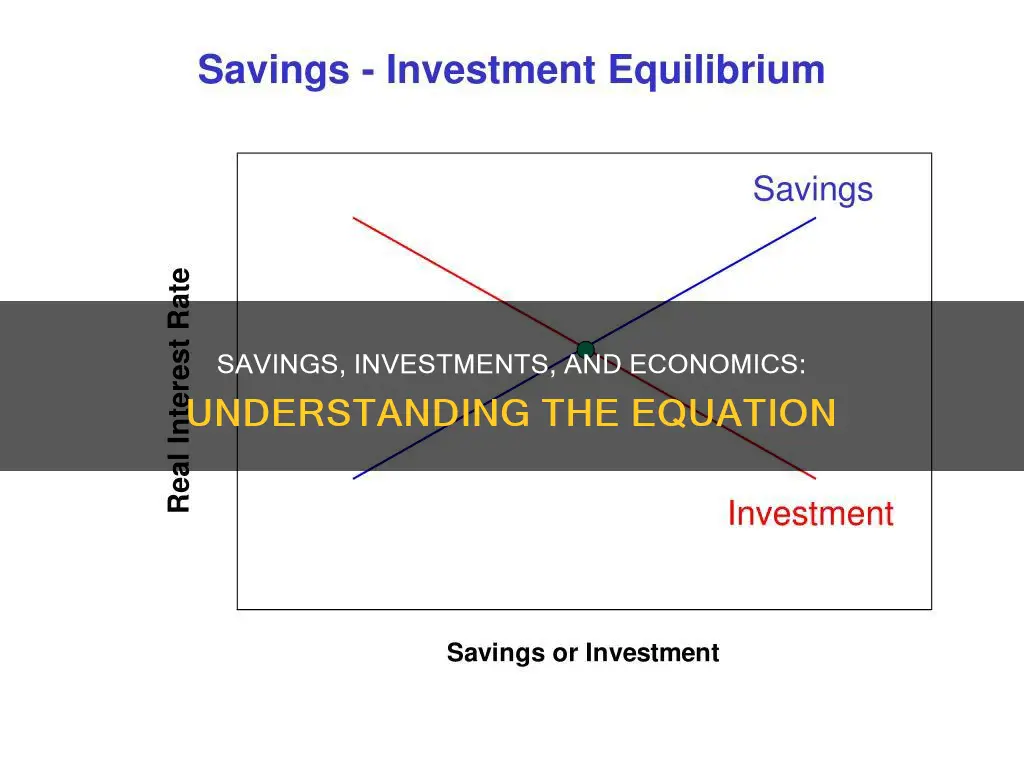

The equilibrium of an economy is maintained when savings are equal to investments. If savings exceed investments, total spending will fall short of output, resulting in downward pressure on prices and reduced production. Conversely, if investments surpass savings, total spending will exceed output, and production rates will need to be increased to maintain equilibrium.

The concept of planned savings and investments introduces the element of intention, where individuals or entities intend to save or invest specific amounts. This adds a layer of complexity, as planned savings and investments may not always align, leading to adjustments in income levels to restore equilibrium.

What You'll Learn

- Equilibrium in the economy occurs when planned investment and planned savings are equal

- When planned savings are greater than planned investment, output will increase to bring the two into balance?

- When planned savings are less than planned investment, national income will increase to bring the two into balance?

- The paradox of thrift: an attempt to increase desired savings is self-defeating and cannot finance desired investment

- Saving is called a leakage because it reduces the amount available for consumption expenditure

Equilibrium in the economy occurs when planned investment and planned savings are equal

Equilibrium in an economy occurs when the desired or planned injections (I) into the economy are equal to the desired or planned leakages (S) out of the economy. In other words, equilibrium occurs when planned investment is equal to planned savings.

Planned investment refers to the planned or desired investment made by firms or entrepreneurs in an economy during a given period, usually a year. On the other hand, planned savings refer to the savings that are planned or intended to be made by all the households in the economy during the same period.

In a simple two-sector income-expenditure model of a pure private economy, total expenditure is comprised of two types of spending: consumption (C) and investment (I). This means that income (Y) is always equal to total expenditure (E), or Y = C + I.

Similarly, income can be divided into two uses: consumption and saving (S). This gives us the equation Y = C + S.

Since Y = C + I and Y = C + S, it follows that C + S = C + I. As C occurs on both sides of the equation, we can say that S = I. Thus, savings and investment are always equal.

However, this equality does not imply equilibrium. Equilibrium requires that desires or plans are realised. If desires are not realised, there will be a push for change as firms and households attempt to bring actual outcomes in line with their desires.

Out of equilibrium, actual savings and investment include both desired and undesired components. Undesired investment (Iu) refers to unexpected changes in inventories, while undesired saving (Su) can occur when goods or services are temporarily unavailable due to shortages or interruptions in production.

Therefore, equilibrium will only occur when actual savings and investment coincide with their desired levels. When desires are not realised, there is disequilibrium, and the economy will adjust until equilibrium is restored.

If planned savings are greater than planned investment, there will be an undesired build-up of unsold stock, leading to a fall in national income and, consequently, a fall in planned savings until it becomes equal to planned investment. On the other hand, if planned savings are less than planned investment, production will have to be increased to meet excess demand, leading to an increase in national income and, subsequently, a rise in savings until savings become equal to investment.

Thus, equilibrium in the economy occurs when planned investment and planned savings are equal. At this point, output, income, employment, and the price level will remain constant.

Savings vs Investments: What's the Real Difference?

You may want to see also

When planned savings are greater than planned investment, output will increase to bring the two into balance

In economics, the concepts of savings and investment are used in two different senses. In the first sense, savings and investments are always equal, irrespective of whether the economy is in equilibrium or not. In the second sense, savings and investments are only equal when the economy is in equilibrium; they are unequal when the economy is in disequilibrium.

When planned savings are greater than planned investment, the economy is in disequilibrium. This results in an undesired build-up of unsold stock, causing a fall in aggregate demand (AD) and a rise in aggregate supply (AS). Consequently, producers will cut down on employment and produce less, leading to a fall in national income and, subsequently, a fall in planned savings. This process will continue until planned savings become equal to planned investment, at which point the economy reaches equilibrium.

To understand this adjustment mechanism, it is important to distinguish between ex-ante and ex-post variables. Ex-ante variables refer to desired or planned magnitudes, while ex-post variables refer to actual magnitudes. In the context of savings and investment, ex-ante savings refer to the amount that households plan to save over a given period, and ex-ante investment refers to the amount that firms plan to invest over the same period. On the other hand, ex-post savings refer to the amount that households actually save, and ex-post investment refers to the amount that firms actually invest.

According to Keynes, ex-post savings and ex-post investments are always equal. This is because ex-post savings constitute a part of national income that is not spent on consumption. Conversely, ex-post investments represent the cost of capital goods purchased to increase production. Therefore, ex-post savings and ex-post investments are two sides of the same coin, and they will always be equal.

However, ex-ante savings and ex-ante investments can differ. This is because savers and investors are typically different people with different motives. Savers include the general public, who save for various objectives and purposes. On the other hand, investors belong to the entrepreneurial class and are guided by factors such as the marginal efficiency of capital and the rate of interest.

When ex-ante savings are greater than ex-ante investments, the level of income falls. At a lower level of income, less will be saved, and ex-ante savings will eventually become equal to ex-ante investments. Conversely, when ex-ante investments are greater than ex-ante savings, the level of income rises, leading to higher savings and, ultimately, equality between ex-ante savings and ex-ante investments. Thus, changes in the level of income serve as a mechanism to bring ex-ante savings and ex-ante investments into balance.

In conclusion, when planned savings are greater than planned investment, output will increase to bring the two into balance. This adjustment process occurs through changes in income, which ensure that ex-post savings remain equal to ex-post investments.

How to Allocate Your Money: Rent, Savings, Investments, and Utilities

You may want to see also

When planned savings are less than planned investment, national income will increase to bring the two into balance

In economics, the concepts of savings and investment are used in two different senses. In one sense, saving and investment are always equal, irrespective of whether the economy is in equilibrium or not. In the second sense, saving and investment are equal only in equilibrium; they are unequal under conditions of disequilibrium.

In the first sense, ex-post savings and ex-post investment are always equal. Ex-post savings are the savings that have actually been made by households in a given period, while ex-post investment is the actual investment made by entrepreneurs in the same period. In this sense, savings and investment are always equal because they are two sides of the same coin. For instance, if a farmer's annual income is Rs. 10,000 and he spends Rs. 6,000 on consumer goods and services, Rs. 1,000 on constructing a well, and another Rs. 1,000 on a drainage system and fencing, then his savings would be Rs. 2,000. The expenditure of Rs. 2,000 on the well, drainage, and fencing is included in savings and is not considered consumption expenditure.

In the second sense, ex-ante savings and ex-ante investment are equal only in equilibrium. Ex-ante savings and ex-ante investment refer to the desired or planned savings and investment for a given period. In this sense, savings and investment can differ because they are made by two different classes of people for different purposes and motives. However, through changes in income levels, there is a tendency for ex-ante savings and ex-ante investment to become equal. When planned investment is larger than planned savings in a year, the level of income rises. At a higher level of income, more is saved, and intended savings become equal to intended investment. Conversely, when planned savings are greater than planned investment, the level of income falls, and at a lower level of income, less is saved, causing planned savings to become equal to planned investment.

When planned savings are less than planned investment, the level of income will rise to bring the two into balance. This occurs because the excess demand caused by higher planned investment cannot be met by current production, leading to an increase in output. The increased production will increase income and, consequently, savings until savings become equal to investment. This adjustment mechanism ensures that the economy returns to equilibrium, where the amount saved is equal to the amount invested.

Investing My Daughter's Savings: Strategies for Long-Term Growth

You may want to see also

The paradox of thrift: an attempt to increase desired savings is self-defeating and cannot finance desired investment

The paradox of thrift, or the paradox of saving, is an economic theory that states that an attempt to increase individual savings can be detrimental to overall economic growth. This theory, popularised by British economist John Maynard Keynes, is based on the observation that total income is equal to total output. Thus, an increase in autonomous saving will lead to a decrease in aggregate demand and gross output, which will, in turn, lower total savings.

The paradox of thrift can be understood through the lens of Keynesian economics, which views the economy as demand-driven. According to Keynes, when people save more during a recession, consumer spending decreases, which slows down economic growth. This is because consumption of goods and services increases national aggregate income, while saving is simply an element of income that is not spent. Therefore, saving money reduces the amount that people spend and invest, leading to lower business revenue and higher unemployment. This, in turn, results in lower economic growth.

The paradox of thrift can be explained by analysing the impact of increased savings on the economy. If a population decides to save more money, total revenues for companies will decline due to decreased demand. This contraction of output leads to lower incomes for employers and employees. Consequently, the population's total savings may remain unchanged or even decline due to lower incomes and a weaker economy. This paradox is based on the proposition that many economic downturns are demand-based.

Criticisms of the paradox of thrift come from neoclassical economists, who argue that savings represent loanable funds, particularly at banks. Thus, an increase in savings should lead to more lending, lower interest rates, and increased borrowing, investment, and spending. Additionally, in an open economy, increased savings in one country can be offset by higher consumption in its trading partners.

In conclusion, the paradox of thrift suggests that an attempt to increase desired savings can be self-defeating and detrimental to economic growth. While saving may be beneficial for individuals, it can have negative consequences for the economy as a whole. This paradox highlights the complex relationship between individual and collective economic behaviour.

Mortgages: Investment or Saving? Understanding Your Financial Future

You may want to see also

Saving is called a leakage because it reduces the amount available for consumption expenditure

In economics, the term 'leakage' is used to refer to capital or income that diverges from some kind of iterative system. Leakages are usually discussed in relation to the flow of income within a system, specifically the circular flow of income and expenditure in the Keynesian model of economics. In this model, leakages are the non-consumption uses of income, including saving, taxes, and imports.

Saving is considered a leakage because it reduces the amount of money available for consumption expenditure. When income is saved, it is withdrawn from the economy's total spending, and a portion of income is excluded from the economic system, reducing the multiplier effect. This, in turn, reduces the amount of money available for spending throughout the rest of the economy.

In a simple two-sector income-expenditure model of a pure private economy, the Keynesian view is that desired investment generates desired saving via income adjustments, rather than being financed by that saving. This model assumes that the productive capacity of the economy remains constant, and only the impact of investment on current demand and income is considered.

The equilibrium condition in this model is that income or output must match desired total expenditure for the economy to be in equilibrium. Out of equilibrium, actual saving and investment include both desired and undesired components. Undesired investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories, while undesired saving can occur when goods or services are temporarily unavailable due to shortages or interruptions in production.

To achieve equilibrium, there must be an impetus for change as firms and households attempt to bring actual outcomes in line with their desires. Firms will respond to unanticipated changes in inventories by adjusting production levels. When firms sell less than anticipated, they will cut back on production to eliminate undesired investment. Conversely, when inventories are unexpectedly depleted due to excess demand, firms will expand production to restore negative undesired investment to zero.

The Keynesian model demonstrates that an increase in desired investment, even if it is not accompanied by an equal intention to save, sets in motion a process by which income adjustments induce the necessary desired saving. This enables the economy to stabilize at a new, higher level of equilibrium income.

To maintain equilibrium in a private closed economy, savings and investments should be equal. If savings exceed investments, total spending will fall short of output, leading to downward pressure on prices. Firms will be forced to cut down on production, resulting in a decline in output and income, and eventually, savings will decrease until they equal investments. On the other hand, if savings are less than investments, total spending will exceed output, and firms will need to increase production to maintain equilibrium. The increased production will lead to higher income and saving until saving equals investment.

Saving and Investment Economics: Core Concepts Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Planned savings are the savings which are intended to be made by all the households in the economy during a period (e.g. a year). Planned investment is the investment that firms or entrepreneurs in the economy desire to make during a period.

Planned savings and planned investment are equal only in equilibrium. If savings are not equal to investment, the economy will not be stable. For example, if savings are greater than investments, the planned inventory would fall below the desired level. Producers will then expand the output, which means more income and a rise in planned investment.

The paradox of thrift is a Keynesian view that a desire to increase savings ends up reducing output, and savings do not increase.