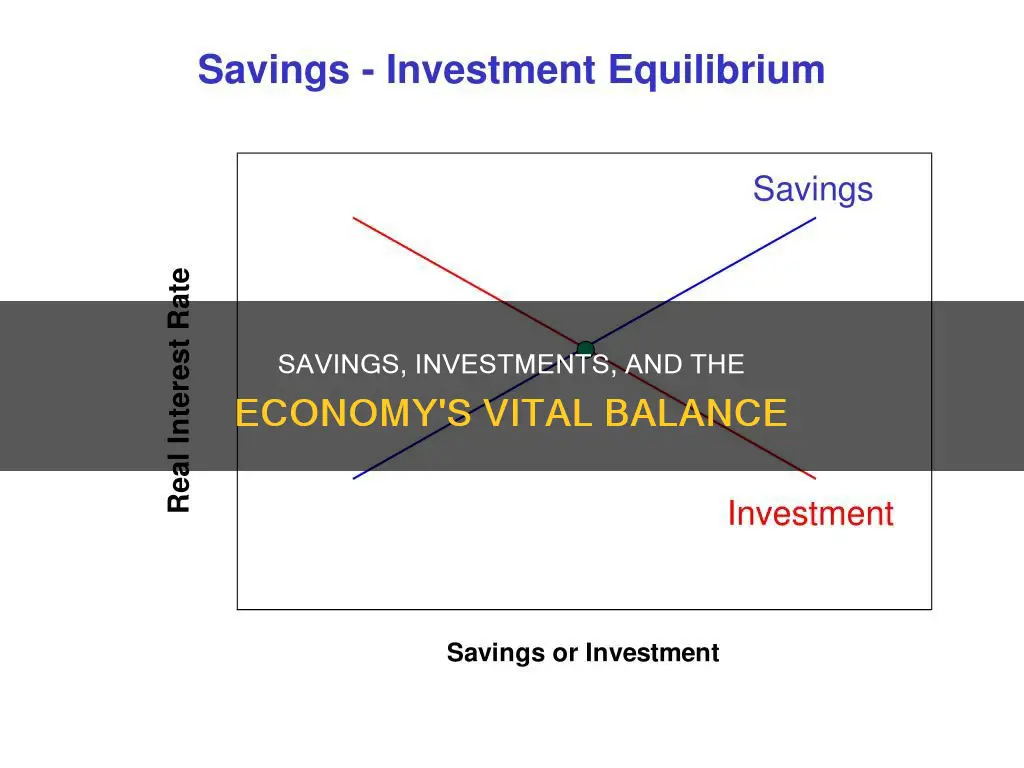

Saving and investment are two fundamental concepts in economics, and understanding their relationship is crucial for comprehending the dynamics of an economy. Saving refers to the portion of income that is not spent on consumption, while investment involves spending on capital goods or the accumulation of inventories. In a closed economy without government intervention, the relationship between saving and investment can be expressed as:

Income (Y) = Consumption (C) + Saving (S) = Expenditure (Y) = Consumption (C) + Investment (I).

This equation implies that saving and investment are equal, i.e., S = I. However, this equality is not as straightforward as it seems, and it has sparked debates among economists, giving rise to concepts like the paradox of thrift.

The equality between saving and investment holds because of how investment is defined. Investment includes both planned investment, which is intentional, and unintended investment, which occurs when there are unexpected changes in inventories. For example, if firms produce more goods than they sell, their inventory increases, resulting in unintended investment. Conversely, if they sell more than expected, their inventory decreases, leading to negative unintended investment.

The distinction between planned and unintended investment is essential because it influences economic equilibrium. When planned savings exceed planned investment, desired inventory levels decrease, prompting producers to expand output. This, in turn, leads to higher income and planned investment, bringing the economy closer to equilibrium. Conversely, when planned savings are less than planned investment, inventories accumulate, indicating that consumption is lower than expected, and there is a gap between aggregate demand and supply.

The relationship between saving and investment is further nuanced by the behaviour of economic agents. Typically, the person doing the saving is not the same as the person making the investment. They have different motives and are linked by a complex financial system, which offers various avenues for parking additional savings, such as holding cash or investing in financial assets.

In conclusion, while the equality between saving and investment holds as an accounting identity, the dynamics underlying this relationship are intricate. The behaviour of economic agents, the role of inventories, and the interaction between saving, investment, and income collectively shape the economic landscape.

What You'll Learn

- Saving is always equal to actual investment, which includes both planned and unintended investment

- If planned savings are greater than planned investments, the planned inventory would fall below the desired level

- When planned savings are less than planned investment, it indicates a situation of less aggregate demand in comparison to aggregate supply?

- Undesired investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories

- The Keynesian view is that desired investment generates desired saving via income adjustments, rather than being financed by that saving

Saving is always equal to actual investment, which includes both planned and unintended investment

In a closed economy, the relationship between saving and investment is an accounting identity. Total income (Y) is equal to total consumption (C) plus total saving (S), but also, total expenditure (Y) is equal to total consumption (C) plus total investment (I). Therefore, S=I by definition.

However, this does not mean that an increase in saving will automatically lead to an increase in investment. If consumers spend less and save more, it does not necessarily follow that firms will decide to buy more capital goods. Instead, firms may accumulate inventories of goods that consumers did not buy, leading to unintended investment.

In the short run, the impact of investment on capacity may be abstracted from, and only its effect on current demand and income is considered. In this case, investment is defined as capacity-expanding expenditure, which includes both fixed investment in plant and machinery, as well as unsold inventories. Undesired or unintended investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories, while undesired saving can occur when goods or services are temporarily unavailable.

Desired or planned investment is assumed to be exogenous, financed independently of current income from past savings or borrowing. Desired consumption and desired saving, on the other hand, are assumed to be endogenous and positively related to income.

In equilibrium, desired saving equals desired investment, and the sum of desired consumption and desired investment equals income. However, out of equilibrium, actual saving and investment can differ from their desired levels due to unintended changes in inventories.

Retirement Planning: 401(k)s, Investing, or Saving?

You may want to see also

If planned savings are greater than planned investments, the planned inventory would fall below the desired level

In a closed economy, the total output (Y) is equal to the total income (Y) and total expenditure (Y). In other words, income (Y) = consumption (C) + saving (S), but also expenditure (Y) = consumption (C) + investment (I). Therefore, saving (S) is equal to investment (I) by definition.

However, this does not mean that an increase in saving must lead directly to an increase in investment. If consumers save more and spend less, the fall in demand would lead to an increase in business inventories. This change in inventories brings saving and investment into balance without any intention by businesses to increase investment.

In the context of planned savings and investments, if planned savings are greater than planned investments, the planned inventory would fall below the desired level. This is because the increase in savings would lead to a decrease in income, which would force an unintended reduction in savings. This would result in a lower level of investment, causing the planned inventory to fall below the desired level.

It is important to note that the relationship between saving and investment is complex and can be influenced by various factors, such as changes in income, consumption, and output.

Investment Opportunities in Pakistan: Where to Invest Your Savings

You may want to see also

When planned savings are less than planned investment, it indicates a situation of less aggregate demand in comparison to aggregate supply

In a simple two-sector income-expenditure model, the equilibrium condition is when income or output matches desired total expenditure. Out of equilibrium, actual saving and investment include both desired and undesired components. Undesired investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories, while undesired saving can occur when goods or services are temporarily unavailable.

In the case where planned savings are less than planned investment, there is excess demand, and undesired saving occurs. Firms respond by adjusting production to eliminate undesired investment and bringing it back to zero. This results in negative income adjustments that wipe out any desired saving that exceeds the level of desired investment.

The Keynesian view suggests that desired investment generates desired saving through income adjustments rather than being financed by that saving. This means that an increase in desired investment that is not accompanied by an equal intention to save can still lead to a process where income adjustments induce the necessary desired saving.

In a more complex four-sector model that includes government and external sectors, the equilibrium condition requires that desires are realized. This can be stated as desired injections being equal to desired leakages. Leakages occur due to taxes and imports during the multiplier process, and the effect of an exogenous change in demand is felt by all leakages.

While an exogenous increase in desired investment can lead to a multiplied change in income, an exogenous increase in desired saving can be self-defeating if it occurs in isolation. However, if the government steps in and increases its net spending, the domestic private sector can achieve higher desired saving alongside strong income.

Saving and Investing: Economy's Growth Engine

You may want to see also

Undesired investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories

Undesired or unintended investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories. In other words, it is the difference between the amount of goods produced and the amount sold. When firms produce more goods than they sell, inventories increase, and unintended investment is positive. Conversely, if they sell more than they produce, inventories decline, and unintended investment is negative.

Unintended investment can occur when customers buy a different amount than expected. For example, if customers buy less than anticipated, inventories build up, resulting in positive unintended investment. On the other hand, if customers buy more than expected, inventories are depleted, leading to negative unintended investment.

Unintended investment can also happen when there is a mismatch between supply and demand. If aggregate output (real GDP) exceeds aggregate expenditures, firms will have produced more than what was demanded, resulting in unsold goods and unplanned inventory accumulation. Conversely, if aggregate expenditures exceed aggregate output, firms will have sold more than they produced, leading to a drawdown in inventory.

Unintended investment has important implications for firms and the economy. When firms sell less than anticipated, they may cut back on production to eliminate undesired investment. This can lead to lower incomes and consumption, potentially reducing savings and investment. Conversely, in the case of excess demand, firms may expand production to meet higher demand and replenish unexpectedly depleted inventories.

It is important to distinguish between intended and unintended investment. Intended investment refers to deliberate actions by firms to adjust inventory levels based on expected demand. Unintended investment, on the other hand, results from unexpected changes in customer demand or market conditions. While intended investment is a form of planned spending, unintended investment can disrupt firms' plans and impact their financial performance.

Savings and Planned Investments: What's the Difference?

You may want to see also

The Keynesian view is that desired investment generates desired saving via income adjustments, rather than being financed by that saving

However, identities do not imply equilibrium. Equilibrium requires desires (or plans) to be realised. Out of equilibrium, actual saving and investment include both desired and undesired components. Undesired investment refers to unexpected changes in inventories, while undesired saving can occur when goods or services are temporarily unavailable. Equilibrium only occurs when actual saving and investment coincide with their desired levels.

The Keynesian assumption is that firms will respond to unanticipated changes in inventories by adjusting the level of production. Desired consumption and saving are assumed to be endogenous and positively related to income, while desired investment is assumed to be exogenous. This leaves the determination of investment open, making the model compatible with a variety of competing theories of investment.

Substituting the behavioural assumptions into the equilibrium condition, rearranging and solving for income yields:

> Income = multiplier x autonomous expenditure

The multiplier is 1/(1 – the marginal propensity to consume).

An example of an exogenous increase in desired investment is as follows:

Let the economy initially be in equilibrium, with income = 500, desired saving = desired investment = 100, and desired consumption = 400. Now imagine that desired investment increases from 100 to 120. The effect of this is that there is excess demand, as desired total expenditure outstrips income. Disequilibrium is also indicated by the undesired saving of 20.

In the second round, the injection of extra spending is received as income by firms producing investment goods and this higher income induces a response from households, who consume 80% of the additional income and save 20%, in accordance with the marginal propensities to consume and save. As a result, desired total expenditure remains above income, but by less than previously due to the leakage to saving. Notice that the increase in desired saving eliminates some of the undesired saving.

The process continues in successive rounds until equilibrium is restored. The example shows income and output adjusting to demand. Notice how income lags demand. The example also illustrates the Keynesian view of how an initial increase in desired investment that is unaccompanied by an equal intention to save nevertheless sets in motion a process by which income adjustments induce the necessary desired saving. This enables the economy to stabilize at a new, higher level of equilibrium income.

In the four-sector model, introducing the government and external sectors adds two more types of expenditure: government spending and exports. There are also two additional uses of income: taxation and imports. These additions give rise to the following identities:

> Income = consumption + investment + government spending + (exports – imports)

>

> Investment + government spending + exports = saving + taxation + imports

>

> (Saving – investment) + (taxation – government spending) + (imports – exports) = 0

Equilibrium requires desires to be realised. This condition can be stated in various equivalent ways:

> Income = desired consumption + desired investment + government spending + (desired exports – desired imports)

>

> Desired investment + government spending + desired exports = desired saving + taxation + desired imports

>

> (Desired saving – desired investment) + (taxation – government spending)* + (desired imports – desired exports) = 0

The first version of the equilibrium condition says that desired total expenditure must equal income. The second version says that desired injections must equal desired leakages. The third version says that the government’s fiscal position must be consistent with the desired net financial accumulation of both the domestic private sector and foreigners.

In the four-sector model, government spending and exports are assumed to be exogenous in addition to desired investment. Taxation and imports are assumed to be endogenous and, like desired consumption and desired saving, positively related to income.

The following model employs these assumptions:

> Desired total expenditure = desired consumption + desired investment + government spending + (desired exports – desired imports)

>

> Desired consumption = autonomous consumption + marginal propensity to consume x (income – taxation)

>

> Desired saving = marginal propensity to save x (income – taxation) – autonomous consumption

>

> Desired investment is exogenous

Substituting the behavioural assumptions into the equilibrium condition, rearranging and solving for income yields:

> Income = multiplier x net autonomous expenditure

The numerator is net autonomous expenditure. The denominator is the reciprocal of the multiplier. The multiplier is smaller than in the two-sector model because of the additional leakages that occur due to taxes and imports during the multiplier process.

An example of an exogenous increase in desired investment in the four-sector model is as follows:

In round 0, the economy is in equilibrium, so desired total expenditure = income and desired injections = desired leakages. Although not necessary for equilibrium, the example starts with all sectoral budgets balanced. This was done to make the impact of the multiplier process on the three sectoral balances obvious.

In round 1, desired investment increases by 50. This causes excess demand as desired total expenditure outstrips income. Disequilibrium is also indicated by the undesired saving of 50.

In round 2, firms expand production to meet the higher demand. The resulting addition to income induces extra desired consumption but also leakages to saving, tax revenue and import spending. Each round, the addition to total expenditure gets smaller and income gradually adjusts to demand.

The causation is the same as in the two-sector model, but the effect of an exogenous change in demand is felt by all leakages. The extra 50 in investment causes a multiplied change in income that eventually increases the sum of leakages by the same amount of 50. In the initial equilibrium, desired injections and leakages both summed to 500. In the new equilibrium at the higher income of 1100, desired injections and leakages both sum to 550.

Notice that the sectoral balances, which were all zero in the initial equilibrium, have diverged. The multiplied increase in income has boosted tax revenues and to a lesser extent imports. As a consequence, the government and foreigners are now in surplus by a combined amount of 35. This is offset by the domestic private sector, which is in deficit, spending more than its income.

The spending and saving behaviour of the domestic private sector was such that most of the leakage created by the higher desired investment went to taxes and imports. The domestic private sector has chosen to draw down some of its accumulated financial wealth. This could go on for a while without causing problems but would eventually create an unsustainable private-debt burden if not reversed, such as occurred in the lead up to the present global financial crisis.

Saving-Investment Model: Understanding the Economics of Macro Theory

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

When planned savings are greater than planned investments, it indicates that consumption in the economy was less than expected, resulting in lower aggregate demand compared to aggregate supply. To bring the inventory back to the desired level, producers expand output, leading to a rise in income and, consequently, a rise in planned savings and investment.

When planned savings are less than planned investments, it indicates that consumption in the economy was higher than expected, resulting in a situation where the planned inventory rises above the desired level. This leads to a decrease in output, which in turn lowers income and planned savings.

In a simple model of a closed economy without government intervention, total output (Y) is equal to total income, which is also equal to total expenditure (Y). Therefore, income (Y) is equal to consumption (C) plus savings (S), and expenditure (Y) is equal to consumption (C) plus investment (I). This implies that savings (S) are equal to investment (I) by definition. However, it's important to note that investment includes "stockbuilding" or "inventory accumulation", which are goods that firms wanted to sell but couldn't.